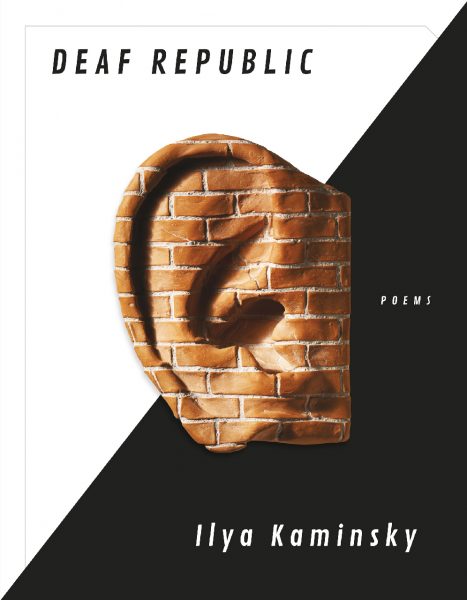

Alexia Kemerling graduated from Hiram College in 2020; she is currently a Junior Associate Editor at Great Lakes Publishing, Ohio Custom Media. Her essay, “Embracing Silence, a Revolution of Self-Acceptance,” was written in response to Ilya Kaminsky’s Deaf Republic. Ms. Kemerling specifically references the poems “Deafness, an Insurgency, Begins,” “Checkpoints,” and “The Townspeople Watch Them Take Alfonso.”

Ms. Kemerling has also provided an audio recording of her reading her essay.

Embracing Silence, a Revolution of Self-Acceptance

By Alexia Kemerling

Our hearing doesn’t weaken, but something silent in us strengthens. –

“Deafness, an Insurgency, Begins,” Deaf Republic by Ilya Kaminsky

I grew up being described as “hearing impaired.” Though when I introduced myself, I often simply said, “I wear hearing aids in both ears.” I wonder if even then, before I’d learned about disability pride, I was subconsciously recoiling from the inherent negativity within much of the language surrounding disability. I never identified with the sense of misfortune implied by the term “impaired.” Yet, the impact of that word left its mark on my confidence, as I fought the urge to see my body as weak, damaged, less than.

Even the more accepted term “hearing loss” doesn’t feel quite right to me. For people who develop hearing disabilities later in life, the term makes sense, but I was born hard of hearing. Is it possible to lose something you never had? The language seems to suggest that to be born with hearing loss is to have lost before you have even lived.

I saw these ideas reinforced not just in my daily life, but in books, too. Disability often appeared not as a character trait, but as a plot device for tragedy or as a metaphor for ignorance. See: “The advice fell on deaf ears.” Then I read Ilya Kaminsky’s Deaf Republic, a book of poems formatted almost like a play. Kaminsky crumbles the cliches and builds a new narrative from the rubble.

Deaf Republic is set in Vasenka, a fictional town under military occupation. The story begins when a soldier publicly murders Petya, a deaf boy, and the entire town becomes deaf. Realistically, the town’s collective disability must be an active choice, yet the persistence of their inability to hear soldier’s orders and their refusal to speak aloud even behind closed doors, safe in the presence of family and friends, makes us begin to see their deafness as an honest reality. We accept this impossible transformation as fact. Deafness becomes their identity.

If all you knew was that the town’s deafness was a response to Petya’s death, you might mistake it as a symbolic way of honoring him. The soldier disliked that Petya didn’t fear the orders that he couldn’t hear, and so the whole town refuses to hear as an act of vengeance. However, shortly after the murder that acts as the story’s catalyst comes a poem titled “Deafness, an Insurgency, Begins.”

Kaminsky writes, “Our hearing doesn’t weaken, but something silent in us strengthens.”

This line could be meant to answer the question of whether or not the town’s deafness is a conscious choice, or a reality made possible by fiction, but for me it reads more as an affirmation—that disability is the opposite of weakness. Rather than focusing on the hearing loss, we see them gain strength in silence. We are meant to admire Vasenka’s muted world, not pity it. Embracing deafness is a revolution.

That idea alone, to me, is a revolution. I have spent most of my life hiding my hearing aids behind my thick hair, learning to piece together the shapes of moving mouths, fragmented sounds, and context clues to avoid asking, “What?”

I wear my hearing aids sixteen, seventeen hours a day, sometimes more. There are times in public when I would love to pop the molds out of my ears, sigh goodbye to the continuous thrum and disruptive clatter of background noise and relax into the quieted abyss. The relief of unplugging is palpable. Yet to be without my hearing aids is to be vulnerable. I risk missing something important or stuttering into awkwardness if someone says something I don’t understand. Thus, I have long made emptying my ears an act of solitude, something I do only when I’m alone.

In Deaf Republic, there is vulnerability in silence, too. In the poem “Checkpoints,” women are stopped by patrols and arrested when they do not hear commands. But there is also power and resistance in this poem. At the same time arrests are being made, Sonya and Alfonso, the story’s central couple, teach sign language in the park, hiding their hands from soldiers. The poem ends by describing deafness as a barricade. While exposing citizens to potential arrest, deafness and secret sign language also create a way to obstruct the mission of the soldiers.

This raises an important theme. I learned to stop seeing my disability as weakness, to stop separating it from the parts of me I considered “good” when I was first introduced to the disability pride movement in college. Acceptance and empowerment blossom from communities created around shared experiences. In Vasenka, the townspeople’s strength comes from being unified in the way they experience the world. Of course, their shared deafness is not their only common identity. They are also shaped by being natives of Vasenka and by becoming rebels in their homeland. They are influenced both by the place and by the way they choose to interact with it. This shared intersection leads to a tight-knit community.

To be a civilian in an occupied land and to be a disabled person in a world designed for the able-bodied is to be treated as an “other”—unwanted, unwelcome. However, even though the soldiers hold the power, the townspeople hold fast to their shared experiences, in turn almost making the soldiers themselves feel ostracized. We see this in the way that the soldiers are quickly angered by their inability to communicate with the townspeople.

Still, there are moments when it can become tricky to determine whether or not the townspeople’s silence is an act of revolution or complicity. In “The Townspeople Watch Them Take Alfonso,” Kaminsky compares the scene of Alfonso’s arrest to a “vaudeville act,” casting our impression of the onlookers in a negative light. They watch but take no action. The poem ends by suggesting that bearing witness and refusing to look away is important, too. The closing line, “Our silence stands up for us,” reiterates the idea of deafness as protest.

Despite the moments where my confidence in interpreting the silence as an act of defiance wavers, one thing is sure: deafness is definitely not a synonym for ignorance in this story, as it so often is in popular culture. The townspeople are aware of the world around them. The story is filled with quiet, yet impactful revolutions. Momma Gayla and her puppeteers subtly teach the town sign language during the day and extract their own violent revenge on soldiers at night behind the stage curtain. Silence, here, does not mean inaction. And even after the country surrenders, and some people forget the hard times, many townspeople still teach their children sign language, the language of resistance, after dark.

Each time I read Deaf Republic I find myself wrestling over how to interpret the town’s deafness. But I am always comforted by the complexity of the metaphors at work. Too often disability is presented in a simplified image. Too often disabled characters are bathed in beautiful pity, displayed in stories about “overcoming,” performed for the consumption of able-bodied audiences. In this story we see characters with many sides, good and bad, weak and strong, and that silence can mean so many things, very few of them negative.

The next time I take out my hearing aids I will think of it less as a form of disconnecting from the world and more as a way of connecting to myself. Rather than focusing on sounds I don’t hear, I’ll focus on all the ways my body has taught itself to adapt, created its own strength.